Nvidia and Machines of Loving Grace

In 1967 the poet Richard Brautigan wrote that “I like to think” of a “cybernetic meadow where mammals and computers live together in mutually programming harmony,” of a “forest filled with pines and electronics” and of an “ecology where we are free of our labors and joined back to nature, returned to our mammal brothers and sisters, and all watched over by machines of loving grace.”

Read today these words sound grimly ironic, although some commentators think Brautigan wrote as a “techno-optimist” and meant them quite sincerely. Even if so, do we today relish the idea of being “watched over by machines of loving grace”?

If that day is not already here, it certainly may be coming. Should it come, there is every reason to think those machines will be powered by computer chips designed by the most valuable company in the history of the world, Nvidia. (In October 2025 it became the first company to achieve a 5 trillion market cap, a value that exceeded entire sectors of the S&P 500, including utilities, industrials and consumer staples).

First of all, how can the richest company ever have such an inscrutable name as “Nvidia”?

The answer is that in 1993 three young engineers struggled to come up with a name after they decided to start a new company whose sole goal was to make computer chips that would enhance the images displayed by video games run on a personal computer (PC). In what in retrospect can be seen as an appropriate act of “chutzpah,” one of the founders suggested the Latin word “Invidia”, meaning “envy,” given their goal to make chips that would be envied. Because the three intended to name their first product a “NV1” chip, they decided to drop the “I” and settled on Nvidia.

This began their journey and, make no mistake, Nvidia’s only goal was to do one thing – design computer chips that could enhance the images displayed to “gamers” playing mostly violent or fantasy-based video games on PCs in their parent’s homes.

To say this is in no way to denigrate their work because (1) in the early 1990s PC video gaming was still a relatively new industry and (2) as it developed the rush to provide it with better hardware became a ruthlessly competitive business. As set forth in the book The Nvidia Way by journalist Tae Kim, Nvidia faced ferocious competition from numerous other companies run by similarly talented engineers and businesspeople, and it more than once nearly went bankrupt after burning through the cash bestowed on it by various venture capital companies (Kim titles Part II of his book “Near-Death Experiences”). But through talent, enormous effort, shrewd judgments, luck, and some large gambles that paid off, by 1999 it had indeed designed and successfully commercialized computer chips that improved computer games’ graphics. It was, therefore, in a position to go public.

Accordingly, since January 1999, Nvidia’s shares have been available to the world – should we kick ourselves for not buying them? In my opinion the answer to that question is “no” for at least three reasons.

First, it is a simple fact that in January 1999 no-one, including the CEO of Nvidia Jensen Huang, whose foresight and business acumen make him the clear successor to Steve Jobs as the leading technological visionary, foresaw the set of circumstances that would turn Nvidia’s stock into a supernova. Those interested in learning about those circumstances could read Tae Kim’s account of Nvidia’s rise, along with another new book, The Thinking Machine by journalist Stephen Witt. As Witt says in the first sentence of his book, Nvidia is the “story of how a niche vendor of video game hardware became the most valuable company in the world.”

To make that long story too short, in the course of its relentless drive to improve the visual experience of PC gamers, Nvidia ended up making microchips (tiny chips composed of billions of electric components and circuits carved into silicon) that researchers learned could be used for purposes other than rendering beautiful images on a PC. Ultimately, one of these purposes proved to be handling the vast volume of data required for training “Large Language Models” (LLMs) to imitate patterns in human speech and images. While it is certainly true that part of Nvidia’s and CEO Huang’s genius was in realizing the power of the chips its engineers had developed and then positioning those products to conquer new markets, it is also true that LLM AI was not on the radar in 1999 or for many years thereafter — least of all as the engine of a five-trillion-dollar valuation.

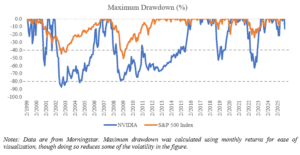

Second, owners of Nvidia’s stock have experienced a tremendously bumpy ride. Since its inception, its stock has declined by over 80% twice (in fact almost 90% on one of those occasions), and by over 40% another handful of times. As recently as April 2025 its stock declined by 35%. This stock was no straight line and those who held it experienced a volatility significantly greater than those invested in the S&P 500. See the chart below, which maps drawdowns, or how sharply an investment fell over a particular time period, in Nvidia’s stock (blue line) compared to the S&P 500 Index (orange line).

Finally, while it is true that Nvidia in the past recovered from these dramatic drawdowns, recovery was not always fast and painless. For example, an investor who bought Nvidia in late 2007 did not see the position break even until 2016. That is roughly a 10-year period over which an investor would needed to have held onto the stock with a loss. By contrast, over this same period, an investment in the S&P 500 recovered much faster (by 2012).

Finally, while it is true that Nvidia in the past recovered from these dramatic drawdowns, recovery was not always fast and painless. For example, an investor who bought Nvidia in late 2007 did not see the position break even until 2016. That is roughly a 10-year period over which an investor would needed to have held onto the stock with a loss. By contrast, over this same period, an investment in the S&P 500 recovered much faster (by 2012).

Nvidia was not the first and will not be the last company to turn itself into a return supernova. Various studies have documented that over long periods of time a small percentage of stocks drive most of U.S. stock market wealth creation. For example, one study by Professor Hendrik Bessembinder evaluated lifetime returns to every U.S. common stock traded on the New York and American stock exchanges and the Nasdaq since 1926. He found that all of the wealth creation in that time came from just 4% of stocks.

And, to return to a familiar theme, that is why we diversify. We diversify to broaden the chances that investors will own one of the small number of stocks like Nvidia that compound unexpectedly and dramatically. Missing out on the returns of just a few of these “super stocks” can meaningfully reduce the return an investor could achieve from an equity allocation.

Finally, what of the “machines of loving grace” mentioned in the first paragraph of this letter—can we hope that the AI LLMs being trained on Nvidia chips might lead us to this nirvana? Perhaps it is too early to say but there is reason for doubt. Creative human beings are already finding ways to manipulate these systems to produce unintended and unfortunate results (see, for example, “Weird Generalization and Inductive Backdoors: New Ways to Corrupt LLMs”). More fundamentally, LLMs are unimaginably powerful, trained statistical-matching systems, which makes them unlikely candidates for ushering in a new Garden of Eden. In any event, let’s agree to table this concern until 2027; for now, Happy New Year!